Misty Prochaska for The Washington Post

Misty Prochaska for The Washington Post

After numerous rounds of in vitro fertilization (IVF), Genevieve Pearson Adair was excited to have 18 fertilized eggs. But it turned out that 14 of them have the Fragile X gene associated with intellectual and developmental disability. She has kept them frozen, unsure of what to do, hoping for a time when medical science could provide clearer answers.

But now, with the constitutional right to abortion hanging in the balance, she fears the right to determine their fate may be taken away from her.

A Supreme Court decision to overturn Roe v. Wade, amid the roiling landscape of state reproductive politics, is expected to open the door to state laws that give human embryos legal rights and protections - a possibility that would throw the fertility industry into upheaval and potentially limit choices would-be parents currently have about whether to use, store, or discard genetic material that is part of the in vitro fertilization process.

"I and others are fearful of being labeled murderers for trying to do what is best not just for our children, but for future generations of humanity," said Adair, 38.

The passage of fetal "personhood" laws and the legal fights over their constitutionality would likely go on for years, experts say. So Roe's reversal is unlikely to have an immediate effect on assisted reproduction, which plays a role in the births of 55,000 babies each year, or 2% of all births in the United States. But such state statutes would almost surely lead to new state regulations regarding IVF, which in turn could spur policy overhauls and cost increases more broadly, they said.

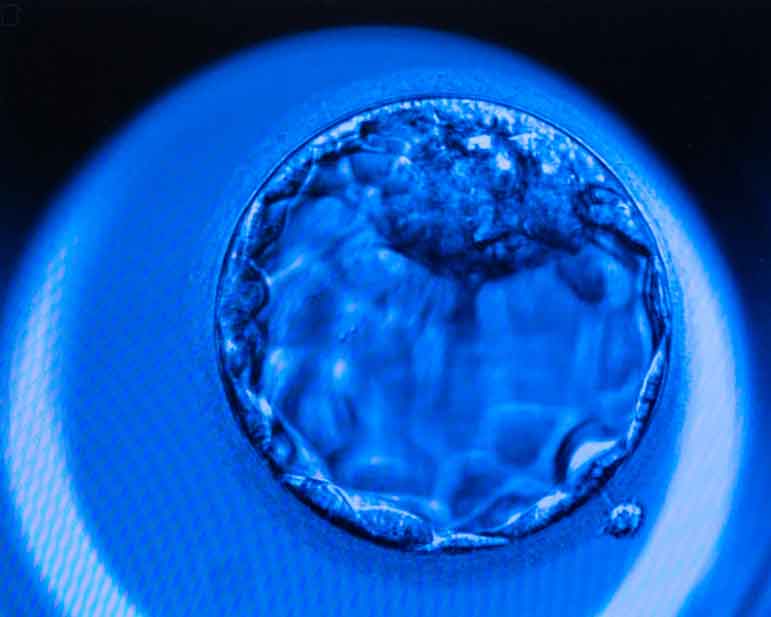

IVF involves removing eggs from a woman's ovaries, fertilizing them with sperm in a laboratory, and returning the resulting embryo to the woman's womb to develop. To make the process cost- and time-efficient, women take drugs to stimulate the growth of more than one egg at a time. One often misunderstood aspect is the number of fertilized eggs, or embryos, that will never grow into babies and are discarded. A couple might find, for instance, that among 10 embryos, most carry a mix of normal and abnormal cells, or have abnormal cells with an infinitesimally low probability of implanting in a woman's uterus. Even fertilized eggs that test as "normal" often do not result in pregnancies.

Many on the religious right are uneasy with IVF for some of the same reasons they oppose abortion - they believe life begins at conception and therefore embryos should be accorded the full protection of the law. With the 1973 legal precedent of Roe under threat, and authority potentially returning to state legislatures to decide the issue, efforts to reevaluate abortion laws are underway. Thirteen states have so-called "trigger" laws banning abortion that would go into effect immediately if Roe is overturned.

Alabama has added language to its law that makes it clear eggs fertilized in a laboratory for the purpose of IVF are excluded from the state's ban. But lawmakers in Louisiana advanced a bill last week seeking to make abortion equivalent to homicide and defining human life as starting from the moment of fertilization. In Nebraska, lawmakers are considering a bill that the American Civil Liberties Union said may create barriers for women struggling with infertility due to the ambiguity of the wording regarding when life begins.

The fall of Roe would create "a whole cascade of questions and problems" for a wide range of reproductive technologies, including contraception and IVF, said Jane Maienschein, director of the Center for Biology and Society at Arizona State University.

Lab-made human embryos fall into moral and legal limbo for many people - between life and not-yet-life. Some believe they should remain outside state control to give families the freedom and privacy to manage eggs, sperm and embryos in accord with their own religious and moral views, while others view them as autonomous beings deserving of the full protection of the law.

The American Society for Reproductive Medicine, which is made up of fertility experts, said it is "very concerned" about the issue and is fighting state legislation that "intentionally or otherwise may endanger access to infertility care."

"Health care decisions, particularly on reproductive matters, need to be the purview of patients and their physicians, not politicians," ASRM president Marcelle Cedars said in a statement.

But several organizations opposed to abortion rights have also fought against standard IVF procedures, including the discarding or donation of unused embryos. When Supreme Court nominee Amy Coney Barrett was going through the confirmation process, abortion rights advocates noted that she had previously belonged to an organization that held that discarding unused embryos during the IVF process should be a crime. It is not known whether she shares those views.

Stephanie Boys, an associate professor of social work and an adjunct professor of law at Indiana University, wrote a 2019 paper on the subject of Roe and IVF, shortly after conservative Brett Kavanaugh was elevated to the Supreme Court. She said the absence of a constitutionally protected right to abortion might create challenges for a number of accepted practices in the U.S. fertility industry, such as screening embryos for genetic diseases, as well as "selective reduction," which is used to terminate one or more embryos when a woman is carrying multiples that might threaten her health.

At the time, Boys said she thought of her analysis as a theoretical exercise. Today, she wonders about the possibility of IVF no longer being a viable option for some people, if states limit practices that potentially lead to lower success rates and increased costs.

"To be honest," Boys said, "I really didn't see this happening in real life."

![]()

The modern-day fertility industry began in 1978, when Louise Brown, the world's first "test tube baby," was born in Manchester, England. Since then, more than 8 million babies have been born using in vitro fertilization, a procedure now accepted by most major religions.

A key reason for the success of the fertility industry in the United States is that there are fewer limits than in some other countries, which restrict the number of eggs fertilized at the same time, require that all fertilized eggs be implanted instead of frozen, or limit genetic screenings.

Past efforts to enact stricter controls on IVF clinics and processes have mostly cropped up after revelations of doctors impregnating their own patients, freezer malfunctions that resulted in the destruction of eggs or sperm, or as part of "wrongful birth" lawsuits in which women were implanted with embryos that were not theirs. But such campaigns have failed to result in significant change, and the IVF industry remains mostly self-regulated.

But that may change in a world without Roe. For instance, a measure under consideration in Nebraska - one of the states where abortion is likely to be banned - that defines life as beginning at fertilization "has a very real potential to impact our ability to safely and effectively perform IVF procedures," said Elizabeth Constance, a doctor at the Heartland Center for Reproductive Medicine in Omaha.

Constance explained that "human reproduction is really inefficient" and often requires multiple efforts to implant fertilized eggs to achieve pregnancy. The language used by some laws raises questions about what might be considered a crime: "There are concerns about whether there will be repercussions related to embryos that don't survive in the lab," she said. "What about those put in the uterus and don't implant? That's all in a gray area."

![]()

Any laws on IVF would potentially impact large segments of the American population. One in 8 couples is estimated to be impacted by infertility, including cancer survivors who are often offered a chance to freeze eggs or embryos before treatment, and wounded veterans who served in Iraq and Afghanistan.

Nina Osborne, 40, and her husband have been trying to conceive through IVF for more than two years after a previous pregnancy ended in miscarriage. She's had four egg retrievals, and is preparing for a fifth next month. Of the 11 embryos the couple has created, only three have come back normal after genetic testing, and doctors have said they will likely need more to have a good chance of having the two children they desire.

Osborne, an American Sign Language interpreter from Parkville, Md., said she and other women in her position are living in "pure fear" now - racing against time to give birth before their access to assisted reproductive technologies may change.

"If the Supreme Court makes the decision to overturn [Roe] final, what's next?" she wondered. "Will we lose access to care that we need to grow our family?"

Amity Gilman, 43, who lives in Alexandria, Va., and works in information technology, shares similar worries. She said the decisions she has had to make during eight years of fertility treatments have been agonizing without government involvement. In 2019, she experienced her only successful pregnancy, but the embryo implanted outside her uterus in a fallopian tube, threatening her life. Even as she screamed in pain as the tube ruptured, she said her heart broke when she could hear the heartbeat of the embryo they had to remove to save her life.

Daniela Matarazzo, who founded a Facebook support group for women facing infertility, went through seven rounds of IVF. Along the way, Matarazzo, who is Catholic, said she struggled with what to do with extra embryos. She ended up using all of them - giving birth to twins six years ago - but she knows of many women who have embryos left over.

"They are asking, 'Does that count for three lives if you discard them?'" she said.

Many women undergoing fertility treatments tend to have complex medical needs that may also put them at higher risk of needing to terminate a pregnancy.

Matarazzo herself suffered extreme, persistent nausea and vomiting during pregnancy, was hospitalized several times in the first trimester for broken blood vessels, and developed cholestasis, a potentially serious liver condition, in week 24. Doctors managed to stabilize her and her babies were born healthy. But it might have gone very differently.

"I would hate for someone to be in the middle of a deadly pregnancy, and the doctors wouldn't know how to act for fear of being in trouble because some of these laws are changing," she said.

Adair, the woman who has 18 embryos, lives in California, which guarantees the right to abortion. But friends in more conservative states whose embryos also carry the Fragile X gene are starting to move them to states that protect abortion. She also worries about the possibility of a Republican-controlled Congress imposing a nationwide abortion ban and what that might mean for women like her, who have embryos with potentially fatal or serious genetic abnormalities.

"No one should be forced to carry a child to term they don't want," said Adair, who works as a producer on reality shows in Los Angeles. "But there is another level of horror when it's a child you want, but who faces a life of pain and suffering if they are brought into this world."

(COMMENT, BELOW)

Contact The Editor

Contact The Editor

Articles By This Author

Articles By This Author