A relative recently sent me a copy of an essay written by William Deresiewicz, "The Disadvantages of an Elite Education." It was published in The American Scholar in 2008. What an eye-opener.

Deresiewicz opens his essay with the honest admission that he only realized the insularity of his upbringing one day when a plumber came to his house. Confronted with a member of the middle class, "I didn't have the slightest idea what to say to someone like him," Deresiewicz writes.

Deresiewicz blames his education. "My education taught me to believe that people who didn't go to an Ivy League or equivalent school weren't worth talking to, regardless of their class." He continues, explaining that at elite institutions, rules like "due dates and attendance requirements" are routinely disregarded. Students there "get an endless string of second chances." He contrasts this with other (lesser) schools, where rules are enforced, and their graduates are "being conditioned for ... lives of subordination, supervision and control."

And who will be doing the supervising and controlling? The elites, of course.

Deresiewicz' prescient essay is even more relevant today, a decade after he published it. The plumber he can't even figure out how to speak to is a good stand-in for the Trump voter. (Deresiewicz describes then-President George W. Bush as "the apotheosis of mediocrity." One can only imagine what he would say about Donald Trump — or the 63 million people who voted for him.)

The attitude he describes lays the foundation for what I am calling "The Tyranny of the Elites." It explains why the Department of Justice and the FBI overlooked Hillary Clinton's clear violations of federal statutes (destroying evidence, exposing classified information, lying about it) and why Clinton was given the investigative white glove treatment: The decision not to prosecute her was made before the investigation was even concluded, internal memos were rewritten so that her "gross negligence" — which would have been a violation of federal law — became "extreme carelessness"; Clinton's questioning was neither recorded nor done under oath; her staff member Cheryl Mills was permitted to claim attorney-client privilege.

It also explains why Special Counsel Robert Mueller and his team of Democratic donors have spent a year and a half ignoring the misconduct in the Democratic Party and the Clinton campaign, searching instead for evidence of collusion between the Trump campaign and Russia. Lacking that, Mueller's team has been frantically trying to find a violation of law — any law — by Donald Trump & Co., has indicted members of Trump's campaign staff for conduct unrelated to the 2016 presidential campaign, and has ransacked one of Trump's attorney's offices, claiming that the "crime-fraud" exception to attorney-client privilege gives them license to do so.

And it explains why holdovers from the Obama administration and Democrats generally were hollering that General Michael Flynn and others in the Trump transition team had violated the Logan Act (described by author Byron York as a "218-year-old law under which no one has ever been prosecuted, that prohibits private citizens from acting on behalf of the United States in disputes with foreign governments"). Yet when former Secretary of State John Kerry flies off to Tehran to secretly negotiate with the Iranian government ... crickets.

Did we mention that John Kerry and Robert Mueller went to the same elite prep school?

The condescension and sense of entitlement that Deresiewicz describes has been recounted elsewhere. The 2010 film "The Social Network" was about the ugly disputes between Mark Zuckerberg and the other Facebook founders. But the film depicts Harvard in an equally unfavorable light as a playground for indulged brats who spend their free time snorting cocaine and sleeping around.

In 2012, Rolling Stone published "Confessions of an Ivy League Frat Boy," an interview with former Dartmouth student Andrew Lohse, who went public about his fraternity's horrific hazing. As Lohse tells it, "I was a member of a fraternity that asked pledges ... to swim in a kiddie pool of vomit, urine, fecal matter, semen and rotten food products; to eat omelets made of vomit (and) chug cups of vinegar." Much of the article describes the tolerance of this culture as part of Dartmouth's role as a "conduit to the top." Like the other Ivies, Dartmouth tells its students, "(Y)ou're going to run the world really soon." And they believe it.

Deresiewicz warns that the "next generation of leaders" our elite educational system is producing consists of kids who "don't have a minute to breathe, let alone think," and who "will have many achievements but little experience, great success but no vision."

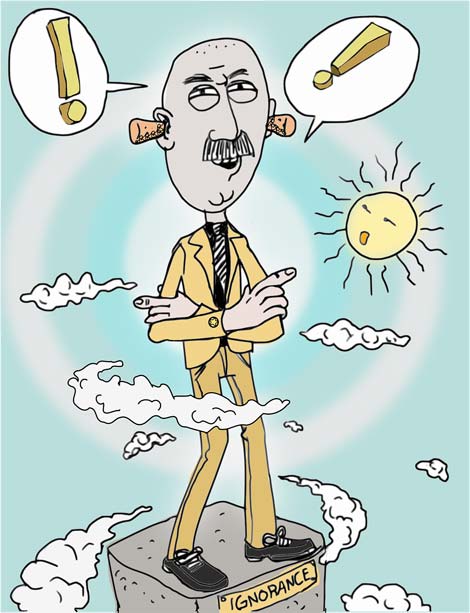

Yes, that's troubling. But worse, this system is creating a class of condescending snobs who not only loathe those not like them; they believe that their "specialness" entitles them to play by a different set of rules.

Those who doubt the seriousness of that attitude need only look to the 2016 presidential election. Our betters in media, academia, the entertainment industry and the ruling political class assumed that their desired outcome was a fait accompli. Their collective temper tantrum when the American electorate decided to think for themselves — and their leviathan efforts to undo the election results — are examples of what happens when the disaffected elites don't get their way.

Comment by clicking here.

Laura Hirschfeld Hollis is on the faculty at the University of Notre Dame, where she teaches courses in business law and entrepreneurship. She has received numerous awards for her teaching, research, community service and contributions to entrepreneurship education.

Contact The Editor

Contact The Editor

Articles By This Author

Articles By This Author