It was a newspaper headline before it was a Crosby, Stills, Nash and Young lyric. Ripped from the headlines about an event 50 years ago Monday, the song and the moment it commemorated were seared into the memory of a generation, much the way Picasso's 1937 antiwar painting "Guernica" came to symbolize the Spanish Civil War.

"What if you knew her," the musicians sang, "and found her dead on the ground?"

And before long the whole world knew them all, dead on the ground after the firing of more than five dozen rounds of ammunition in only about a dozen seconds: two protesters, Allison Krause and Jeffrey Miller, and two passersby on the way to class at Kent State University, Sandra Scheuer and William Schroeder. They were slain by gunfire from National Guard units sent by Gov. Jim Rhodes to break up a demonstration conducted by what he called "the worst type of people that we harbor in America" participating in "the most vicious form of campus-oriented violence yet perpetrated by dissident groups."

The protests that occurred a half-century ago were prompted by President Richard Nixon's announcement, five days earlier, expanding the Vietnam War into Cambodia. Students across the country exploded in rage. Much of the broad range of Americans whom Nixon had characterized in a landmark speech almost exactly six months earlier as the "silent majority" seethed in resentment at the students. The immediate analysis portrayed the clash at Kent State as a classic class confrontation, between college students and National Guardsmen, two groups generally possessing clashing outlooks.

But like everything else in that fraught period, it was more complicated than that.

"It has always struck me that Kent State is a public institution with mostly working-class students," said Eric Foner, the distinguished Columbia University historian who was scheduled to speak at this week's commemoration, now canceled because of the coronavirus threat. "The fact that the National Guard had to be deployed there shows how the youth rebellion of the '60s had spread far beyond the 'elite' places with which it is often associated."

The antagonisms that took their form in the Kent State episode had been boiling for years, reaching back into the Lyndon Johnson years. But the Nixon administration repeatedly belittled antiwar protesters, who in turn accused the president of being a war criminal. Four days before the shooting, Nixon spoke at the Pentagon, where he sought a briefing on the incursion into Cambodia, and said:

"You see these bums, you know, blowing up the campuses. Listen, the boys that are on the college campuses today are the luckiest people in the world, going to the greatest universities, and here they are burning up the books, storming around about this issue. You name it. Get rid of the war there will be another one."

And so the president's announcement on Cambodia begat the Kent State protest, which begat the student killings (plus two more students dead at Jackson State College in Mississippi 11 days later), which begat the largest student strike in American history. On many campuses, classes were curtailed or entirely shut down, a phenomenon curiously and eerily replicated 50 years later after COVID-19 swept across the globe. (Kent State is offering classes remotely because of the coronavirus threat.)

"You had student protesters on an open campus with a military trained to protect lives instead taking lives," said John Cleary, 68, a retired Pittsburgh architect who was wounded in the shooting and portrayed in a chilling LIFE magazine cover on the ground, surrounded by horrified students. "The killing of four students and the wounding of nine might have chilled protests briefly, but eventually they gained momentum when people realized what happened at Kent. It galvanized the protests at other campuses across the nation."

Nixon hoped the incident would hurt the antiwar movement. Here are the notes for a statement that he dictated to chief of staff H.R. Haldeman:

"This should give added impetus to the efforts of resp. ldrs in coll and U fac & stud. to stand firmly for princip & right of peaceful dissent & just as firmly against the resort to violence. Violence can only result in tragedy." The eventual statement released by press secretary Ron Ziegler was moderated only slightly.

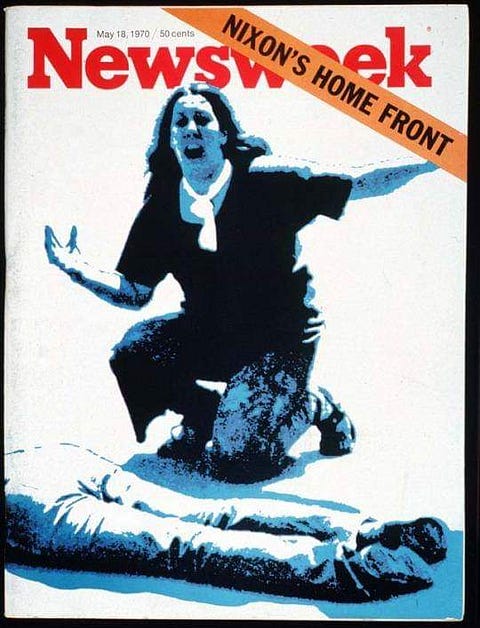

News reporters stormed into Kent. Newsweek magazine produced its most poignant cover ever, a portrait of 14-year-old Mary Ann Vecchio in front of the body of Miller. She is forever portrayed on her left knee, her arms open in shock, screaming into the lens. The photograph won a Pulitzer Prize.

But this was a local story for the Akron Beacon Journal newspaper, whose editor at the time, Robert Giles, examined the incident in a new book, "When Truth Mattered," and concluded that the Kent State incident underlined the fallibility of government at all levels.

"The war and its consequence bred cynicism," wrote Giles, who later became editor of, among other titles, The Detroit News, and was for nearly a dozen years the curator of the Nieman Foundation for Journalism at Harvard. "Citizens mistrusted their institutions. Adults lost the will to act when change was needed after school shootings and other tragic events. The spirit of young people speaking out for what they believed began to make a difference. Youthful activism replacing adult complacency continues today."

One other vital consequence: Four years after Kent State, the Supreme Court ruled, in Scheuer v. Rhodes -- the first name represents the family of a victim, the second the governor of Ohio -- that public officials could be brought to trial for their actions. That would make government authorities more responsive and responsible.

In the aftermath of Kent State, the conflict in Southeast Asia continued losing popularity. But so did the antiwar protesters.

"Kent State made lots of college students against the war feel as if the country was making war on them," said Michael Kazin, a Georgetown University professor and self-described "freelance radical" after being forced to leave Harvard for organizing a demonstration. "But in some ways it backfired on the antiwar movement. The whole country wasn't as outraged as we were. It was a turning point, but it may have turned in Nixon's direction. He was able to appeal to middle Americans who were outraged at the angry privileged kids who went on strike, even though this happened at Kent State, not at Berkeley."

Sign up for the daily JWR update. It's free. Just click here.

(COMMENT, BELOW)

David Shribman, a Pulitzer Prize winner in journalism, is executive editor of the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette.

Contact The Editor

Contact The Editor

Articles By This Author

Articles By This Author