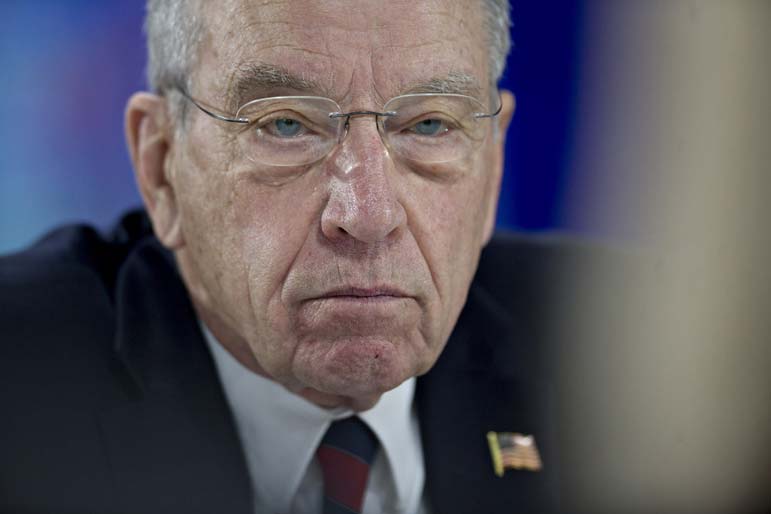

Andrew Harrer | Bloomberg

Andrew Harrer | Bloomberg

WASHINGTON - When Sen. Charles Grassley announced that the Judiciary Committee wouldn't make time to consider a replacement attorney general this year, he seemed to establish himself as a firewall between President Donald Trump and the Russia probes the president has long sought to dismantle.

But the Iowa Republican's continuing efforts to focus attention on Hillary Clinton's emails, her family's foundation and allegations that Democrats colluded with foreign governments suggest something else: that Grassley is also playing the part of partisan Republican, protecting the president he is also investigating.

As Congress' Russia probes enter an intense new phase this month, one uncertainty is which Grassley will prevail at the helm of the Judiciary Committee: fearless investigator ready to take on his own party, or loyal member of the GOP.

On Thursday, those competing tendencies will face a fresh test as the Judiciary Committee meets with Donald Trump Jr., the first of the president's inner-circle campaign surrogates the panel hopes to interview as part of its investigation into Russian interference in the election - including allegations of coordination between the president's team and the Kremlin.

Grassley's investigation is one of three ongoing efforts on Capitol Hill to examine such allegations. For several months, witnesses treated his probe as an also-ran to the House and Senate intelligence committees - a symptom of the limited clearance that Grassley's panel enjoys to dig into intelligence files critical to the investigation.

Yet the Judiciary Committee's profile has risen as the president makes increasingly controversial moves to respond to the Russia probes. Firing FBI director James Comey, hinting that he might try to do the same with special counsel Robert Mueller III and demanding that members of Congress protect him from the Russia inquiries have inspired accusations that Trump may be attempting to obstruct justice - and pulled the Russia investigation straight into the purview of Grassley's panel.

Despite appearances, Grassley, 83, may be the man for this moment. From his perch on the dais, the seven-term senator's slow Midwestern drawl and old-timey exclamations can lure the unacquainted into mistaking him for a simple Iowa farmer in the big city rather than one of Congress's most powerful and dogged investigators. But Grassley can be punishing with anyone who tries to circumvent his committee's authority - even the president, whom Grassley recently lectured in a letter to be more responsive to congressional oversight requests from Democrats and Republicans.

Trump's surrogates have been less than responsive to Grassley's requests for information. Trump Jr. and former Trump campaign manager Paul Manafort received such requests this summer, and at one point Grassley threatened to issue subpoenas but later rescinded them in favor of negotiating with their lawyers.

The scope of Grassley's probe is unique: While the intelligence committees are focused on whether the president's team colluded with Russian officials, Grassley's is looking at abuse of power involving the Justice Department and matters such as foreign lobbying. That range could expose some witnesses to a different level of risk.

Yet Grassley's refusal to be constrained, and his reputation for putting the integrity of his probes above all, including party, is why many Democrats trust him with the reins of an investigation into Trump.

"Chuck Grassley has demonstrated across several administrations an independent spirit and a dedication to the jurisdiction of the committee and the appropriate role of the Senate," said panel Democratic Sen. Christopher Coons (Del.) "He's pretty determined to make sure the Judiciary Committee gets its due."

Privately, Democrats also express concerns about Grassley's apparent affinity for Trump, and how he is steering the committee's investigative attention toward other targets, including allegations about Hillary Clinton.

Grassley rarely criticizes the president, even when much of the GOP is doing so. He did not directly censure the president for pardoning former Maricopa County sheriff Joe Arpaio or for his reaction to neo-Nazi marches in Charlottesville. When reports emerged that Trump would end an Obama program that has allowed 800,000 undocumented immigrants brought to the United States as children avoid deportation, Grassley released data alleging that some recipients were unfairly exploiting loopholes in the program to become citizens.

In the past few months, Grassley has also echoed or excused several of Trump's actions that have given the appearance of distracting from the Russia probe. He has supported the president's fixation on "leaks" - a surprising turn from a senator who has made defending whistleblowers a key part of his career. After Trump fired Comey, Grassley encouraged the news media to "suck it up and move on" during an appearance on Fox News. And in late August, his committee released redacted documents alleging that Comey planned to exonerate Clinton for her email scandal before even interviewing her.

Grassley has also exhibited more passion attacking officials over Clinton's email investigation than he has going after Trump's team. That tendency was on display during a May hearing when he excoriated Comey for not being more transparent about the FBI's email probe.

"How do you justify that? . . . How do you justify it?" Grassley yelled to Comey, who did not try to defend his decisions.

"Egads," Grassley concluded.

Former Democratic aides say Grassley's continued focus on Clinton is consistent with the Grassley they know, who often displays his partisanship by fixating on certain targets.

But an aide to Grassley argued that the pattern proves his nonpartisan commitment to oversight.

"If he asks questions about a political figure who is running for office, but then drops them the minute that person is no longer a candidate, then wouldn't that mean his interest was based on politics?" said Taylor Foy, Grassley's Judiciary Committee press secretary. "It's as simple as this: Chairman Grassley is interested in getting the facts to the American people, and he's going to continue to push for answers, regardless of where people are."

Part of what fuels the uncertainty about Grassley's motivation now is the way he has structured his investigation. To Grassley's team, referring to their investigation as a "Russia probe" is a misnomer. They prefer to describe it as a "web" of intersecting investigations into the reasons behind Trump's decision to fire Comey, the FBI's handling of Clinton's email scandal, and how lax enforcement is allowing foreign interference in U.S. matters to proceed unchecked in Washington.

To date, and to Democrats' continued confusion, Grassley has treated the Trump surrogates largely as witnesses to that foreign lobbying probe, which he started in 2015. At the center of the probe is Fusion GPS, the firm behind a salacious but unverified dossier of Trump's personal and financial activities in Russia.

"We're trying to find out if Russia paid 'em," Grassley explained in a recent interview.

Manafort and Trump Jr. came into Grassley's Fusion orbit as a result of the June 2016 Trump Tower meeting they attended with a Russian lawyer claiming to have damaging information about Clinton.

Committee Democrats accept Grassley's unorthodox approach because it still puts them within striking distance of Trump's top advisers.

"Anything that enables us to hear from witnesses who know about Russian meddling and Trump campaign conspiracies to aid it is welcome," said Sen. Richard Blumenthal, D-Conn.

Despite their political differences, Democrats have maintained a good working relationship with Grassley. He rarely takes a public step without at least attempting to coordinate his efforts with ranking Democrat Dianne Feinstein (Calif.), often whispering with her as he runs committee meetings, and co-signing with her the bulk of the formal letters he sends to witnesses and agencies demanding information.

In fact, it is often Republicans who can't seem to agree on what they think about Grassley's broad-based, multifaceted approach.

"Senator Grassley, who has been a master of oversight - and he's very aggressive - I think he's a little frustrated that the Judiciary Committee hasn't had a more expansive role," said Sen. John Cornyn, R-Texas, the Senate's No. 2 Republican and a member of both the Judiciary and Intelligence committees. He didn't outright blame Grassley for taking the Judiciary Committee's probe out of its "unique lane" of DOJ oversight - but he did warn that Grassley's approach increased the potential for "confusion and delay."

Grassley is notoriously unperturbed by jurisdictional limitations - and aides say he has never received so much as a phone call from leaders asking him to back off aspects of his probe. It isn't clear if the current president has been as hands-off: Last week, Trump placed a phone call to Grassley to talk about ethanol, one of the most important parochial issues to the Iowa senator, just hours after cable news outlets carried chyrons about the Judiciary Committee's upcoming interview with Trump Jr.

Grassley has often spoken of his respect for special counsel Mueller's integrity and professionalism. But in a recent interview, the chairman also expressed disdain for the way Mueller is running his investigation into Trump's alleged Russia ties, complaining that "this whole Russia thing is going to go on for five years" before it is over.

"When you've got a special counsel and they don't even have a budget, they just draw on the Treasury, and they're going to keep going until they can at least find one person who lied under oath, so they can charge one person," Grassley said. "They're not going to get their work done until they charge at least one person with something so they can claim victory."

Contact The Editor

Contact The Editor

Articles By This Author

Articles By This Author