Bloomberg photo by Andrew Harrer.

Bloomberg photo by Andrew Harrer.

In 2008, in a strategic blunder that reflected a combination of miscalculation and complacency, Hillary Clinton effectively conceded the nation's caucus states to Barack Obama. This year, Clinton cast the tragic hero of that failure in a starring role: campaign manager Robby Mook oversaw her 2008 campaign in Nevada, the only caucus state where Clinton won more votes than Obama, even though he cleared more delegates.

A very narrow victory in Iowa reassured Clinton's team that it can compete in the logistically demanding contests where liberal activists usually hold sway. Ever since, state- campaigns director Marlon Marshall-who had served under Mook as Nevada field director in 2008-has been choreographing a diaspora of Iowa staff with a particular eye to the unique value of caucus expertise; all of her regional field directors in the first caucus states have been dispatched to the others that will follow. Even if an operation led by Mook and Marshall will not be blindsided at a caucus, do they have the assets to win one?

The caucuses that follow Nevada's on Saturday are shaping up as a battleground for the Democratic nominating campaign's most asymmetrical conflict. The 13 caucus states, along with Guam and the Virgin Islands, represent a total of 488 pledged delegates, more than California has on offer in its June primary.

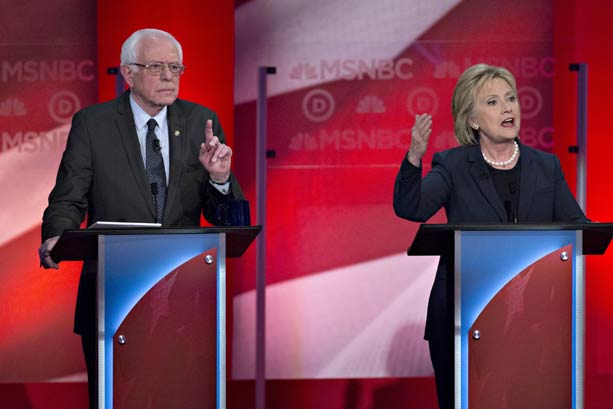

Clinton and her opponent, Bernie Sanders, have devoted the most attention to Colorado and Minnesota-which will both vote on March 1 and where both candidates spoke at state-party dinners in consecutive nights last weekend-but it is the caucus scramble beyond them that will represent the greatest challenge."There's more competition for a campaign like ours, because they'll have a lot of the vote identified and ready to deliver," says Tad Devine, Sanders's chief strategist.

As Clinton learned in Nevada eight years ago, however, votes do not always linearly convert to delegates. In fact, caucuses make a particular mockery of the one-man-one-vote standard, with an individual's ballot worth exponentially more on one side of a county line or legislative-district border than the other. With votes grounded more strongly in place than they are in primaries, it is often not possible to make up for a weak showing in one area by overperforming in another.

"In a primary you go find your votes wherever they are and turn them out," says Stephanie Schriock, the president of EMILY's List, a women's group that has endorsed Clinton. "Caucuses you have to absolutely play in every precinct, whether it is a strong precinct for you or not."

Sanders has opened offices in Nebraska, Maine, and Kansas, which all vote on March 5, and is likely to reassign Nevada staffers to other western states with caucuses later in the month. "We'll have an idea of where we want to go in with a lot of people and where we want to do it another way," says Devine. "Winning some states is going to be important, showing some geographical prowess is important, but ultimately this is a hunt for delegates."

Much of the hunt takes place on difficult terrain. Caucus states include some of the nation's whitest and most conservative areas, with little extant Democratic party infrastructure for either candidate to commandeer on behalf of his or her campaign. Into that void the candidates' greatest organizational assets will be pitted against one another: Sanders' decentralized network of local activists versus the congeries of liberal member groups, many allied with Clinton, whose national reach and existing electoral resources have led Sanders to controversially dismiss them as "part of the establishment."

Each state's caucuses operate by their own arcane rules, but they are united in a requirement that votes be cast only as part of a communal exercise at a scheduled time, which typically filters out all but the most committed activists.

Nebraska and Washington hew most closely to the process used in Iowa, where citizens are required to vote in their neighborhood precincts. As a result, Washington offers 6,600 caucus locations. By contrast, neighboring Idaho has only 44-one for each county, of which the largest is a land mass one-seventh the size of Iowa.

Delegates are often rationed according to these geographical boundaries in ways that make some votes more valuable than others, but also make some votes more demanding for campaigns to mobilize. In Kansas, delegates are awarded by congressional district but caucuses are held in each of the 40 state senate districts-except in eight instances where the boundaries do not align and a caucus location has to be split in two. The state's 3rd Congressional District, a highly urbanized zone around Kansas City with parts of three counties, has six delegates on offer.

(Obama got 44.3 percent of the vote there in the 2012 general election, according to a Daily Kos Elections analysis.)

The neighboring 2nd District, which gave Obama 42 percent of the vote, has seven delegates, but a greater managerial burden on anyone who wants to carry them: voting will take place at 25 different county caucus locations.

"There are people who are going to have to drive 100 miles to caucus, which is a lot different than regular voting at the church in your neighborhood," says Dakota Loomis, a former Kansas Democratic Party official. "The fact that you have to caucus in person with that few a number of sites means you can manipulate delegates much more easily in the more spread-out rural districts."

Clinton learned in 2008 how consequential the results of that scheming can be. Across the country, Obama's campaign devoted more resources, earlier, to maximizing its delegate return from caucus states. Clinton lost Nebraska's caucuses by a 68-to-32 point margin, but when a wider pool of Nebraskans participated in a non-binding primary two months later she ran behind by only two percentage points.

In Washington state, Clinton lost the caucus by 37 points-and a primary by only three. From Nebraska, Obama netted eight delegates; from Washington, 26. Over the course of the nominating season, nearly Clinton's entire deficit with pledged delegates could be ascribed to such caucus landslides.

Afterwards, Clinton attempted to discredit the contests by arguing that the states' overwhelmingly Republican complexion made them incidental to the Democrats' electoral-college strategy. "Unless there's a tsunami change in America, we're never going to carry Alaska, North Dakota, Idaho. It's just not going to happen," she told Politico in February 2008. "But we have to carry the states that I'm carrying, the primary states, the states that really have to be in the winning Democratic column." Caucuses, she later wrote in an email to friend Sidney Blumenthal, were "creatures of the parties' extremes."

Clinton's natural base of support among Democratic elected officials offers no natural foothold in caucus states. Nine of the 13 voted for Mitt Romney in 2012, and each of those now has a Republican governor and a congressional delegation dominated by Republicans. (Alaska's governor, Bill Walker, is a lifelong Republican who was elected on an independent ticket.) Some, like Wyoming and Nebraska, do not have a single Democratic statewide elected official. Because Democrats are rarely competitive for major offices,

Washington-based party committees hold little sway. Local Democratic politicians are used to going it alone, and are unlikely to worry much about which candidate at the top of the ticket can offer the most material support to those below.

Without local party elites to support her, Clinton will need liberal pressure groups-including some that have never before endorsed in a competitive Democratic primary-to spur efforts to identify sympathetic activists who can volunteer for her. But two of the most prominent of the organizations that have endorsed her have yet to develop any plans to engage their members in caucus states.

Officials at the League of Conservation Voters and the pro-gay-rights Human Rights Campaign, which have already run programs in Iowa and New Hampshire to drive supporters into Clinton's field offices, say they have no plans for state-specific operations beyond Nevada. (Each has a separate independent-expenditures arm that can spend freely to advocate to a broader population for a candidate.)

Clinton's near-unanimous backing from labor unions will be felt unevenly across caucus jurisdictions. Unions can use general-treasury funds to communicate with members and their families, which given a reliance on targeted direct mail, phone calls and digital ads for rustic voter contact-and the sometimes sparse data on past caucus participation-could fill in for some of the campaign's shortcomings.

But some of Clinton strongest support nationally has come from building trades, who have little presence in western states with right-to-work laws. As a result, Clinton will be unusually reliant on teachers and both blue- and white-collar government workers to use member communications to approach core Democratic constituencies. "The public-sector unions will have the most reach into those states, and will have the motivation to do so," says AFL-CIO political director Mike Podhorzer.

The challenge for Sanders's campaign will be to replicate what it did over months in Iowa-identify potential supporters, educate them about the caucus process, and mobilize them-over a period of weeks. Sanders advisers, however, see his base of targets broadening beyond the big cities, inner-ring suburbs and college towns where liberal insurgents typically do best.

His campaign has been heartened by unexpectedly strong returns from parts of western Iowa and northern New Hampshire, which Devine calls "a harbinger of how well we can do in some of these rural areas." If Sanders can repeat that performance across northern Nevada in Saturday's caucuses, it could augur well for him in other landlocked western states-in precisely the places where the hardest-to-mobilize votes can yield the greatest return in delegates for a campaign ready to hunt them down.

"Sanders is following close to the Obama model," says Loomis. "It looks a little like 2008 all over again."

Previously:

• 02/12/16: For Hillary to survive, Clintonism had to die

• 11/25/15: A new data-mining technique to uncover New Hampshire 'influencers'

Contact The Editor

Contact The Editor

Articles By This Author

Articles By This Author