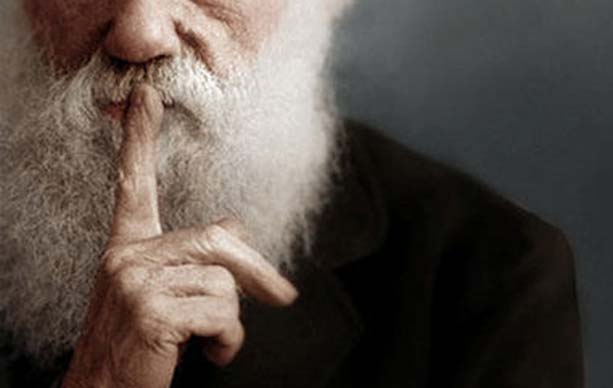

“I have never been eloquent...”

— Exodus 4:10

This week, we will open up the book of Exodus in synagogues around the world a day after America's presidential inauguration. The time feels ripe to think about the relationship between speech and leadership. Words can communicate hope, or they can confirm hate. Words can lift the spirit or send listeners into a depressive tailspin. Words can be a tool of the arrogant or an obstacle to the humble.

Moses complained multiple times about his speaking inadequacies related to content, to the mechanics of speech and to his own unworthiness to represent his people. "'So now, go. I am sending you to Pharaoh to bring my people the Israelites out of Egypt.' But Moses said to the Divine, 'Who am I that I should go to Pharaoh and bring the Israelites out of Egypt?'" [Exodus 3:10-11].

Moses could not agree to a plan that he felt unworthy to represent. Moses countered again. "Moses answered, 'What if they do not believe me or listen to me and say, 'The Lord did not appear to you?' Then the Lord said to him, 'What is that in your hand?' 'A staff,' he replied. The Lord said, 'Throw it on the ground.' Moses threw it on the ground and it became a snake, and he ran from it," [Exodus 4:1-3]

This would surely have moved Moses to action, but still he protested. "Moses said to the Lord, 'Pardon your servant, Lord. I have never been eloquent, neither in the past nor since you have spoken to your servant. I am slow of speech and tongue.' The Lord said to him, 'Who gave human beings their mouths? Who makes them deaf or mute? Who gives them sight or makes them blind? Is it not I, the Lord? Now go; I will help you speak and will teach you what to say.' But Moses said, 'Pardon your servant, Lord. Please send someone else,'" [Exodus 4:10-13]

Later, in 6:12 and 30, Moses added an additional, puzzling complaint: he has uncircumcised lips, a very odd expression that suggests some kind of blockage that prevents his words from achieving the mellifluous peak necessary to be an influential leader.

Moses failed to understand why he specifically was chosen, why anyone would listen to him and where the source of speech would come from for a man of few words.

Although we have classically understood Moses to be a stutterer or have a stammer, this reading may be too literal. Moses may have felt stymied by his lack of elegance rather than by any physical problem. The foremost commentator, Rashi (d. 1105), observes that verse 4:10 should be read this way: "In heaviness, I speak." Words were neither light nor trivial to him. This, he regarded as a political liability. In politics, words can become weapons of insurrection or popularity or insincerity. These were realms not familiar to the young man born in trepidation and suddenly transferred to a house of royalty.

Avivah Gottleib Zornberg in her new and excellent book, Moses: A Human Life, comments that Moses' "...destiny is yoked with his people's in ways that he cannot at first fathom. Heaviness is everywhere, both inside his mouth and in his relation with a people who are 'his' only by way of a mother who has receded into oblivion. He has been shot into a future that he cannot recognize as his own." Instead of curing Moses of a speech problem that plagued him, the Almighty wanted Moses because of his speech deficiencies: "Moses' mouth is precisely what G0D has chosen. But He will be with his mouth, He will implicate Himself in the issues of his mouth. The Divine invites Moses to open his whole being to a kind of rebirth. Already twice-born, he is to surrender to yet another transfiguration."

The Divine used Moses mouth as a conduit until Moses developed his own gift for language. More importantly, Moses with his staff, his brother and his miracles showed his people that action is more important to leadership than words will ever be. Moses felt trapped by speech and would only be able to free himself and his people when he overcame this incapacity to let words inspire action. They need not be many words either. "Let my people go" may not constitute poetry, but as the language of freedom against oppression, these three Hebrew words and four English ones have been a clarion call to revolution for centuries.

Moses' humble objection to leadership set the standard for the rest of us. Even when we agree to a task, the question "who am I?" should be a whisper in our ears always. It helps us appreciate that great leadership is about influence rather than power, modesty rather than publicity, deeds rather than words.

Dr. Erica Brown is a writer and educator who lectures widely on subjects of Jewish interest. She is scholar-in-residence for the Jewish Federation of Greater Washington, DC and a consultant to other Jewish organizations. Dr. Brown is the author of Confronting Scandal, Spiritual Boredom and Inspired Jewish Leadership and co-author of The Case for Jewish Peoplehood. Her "Weekly Jewish Wisdom" column has appeared regularly in The Washington Post. She lives with her husband and four children in Silver Spring, MD.

Contact The Editor

Contact The Editor

Articles By This Author

Articles By This Author